Garden books and winter go together. After the garden has been covered over, – first by autumn leaves, then frost, and finally a dusting of snow – what’s left for a gardener to do until March but read?

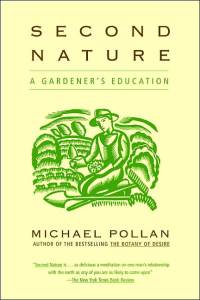

Of course, by now someone has told you that you HAVE to pick up a copy of The Omnivore’s Dilemma (if you haven’t already). But before The Omnivore’s Dilemma; before “Eat Food. Not Too Much. Mostly Plants.” was made into a bumper sticker; before he wrote the letter telling the Obama’s to plant veggies on the White House lawn; before all that Michael Pollan wrote a book called Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education. And by any standard it was, and remains, a beautiful piece of writing.

With the harvest moon, which usually arrives towards the end of September, the garden steps over into that sweet, melancholy season when ripe abundance mingles with auguries of the end anyone can read. Except, perhaps, some of the tropical annuals, which seem to bloom only more madly the closer the frost comes. Mindless of winter’s approach and the protocols of dormancy, the dahlia and the marigold, the tomato and basil, make no provision for frost, which might be a month away, or a day. The annuals in September practice none of the inward turning of the hardy perennials, which you can see slowing down, taking no chances, turning their attention from blossom and leaf to root and stashed starch. But instead of battening down the hatches, saving something for another day, the annuals throw themselves at the thinning sun, open-armed and ingenuous. On those early autumn days when frost hangs in the air like a sword of Damocles, evident as sunlight to the lowest creature, is there anything more poignant than a dahlia’s blithe, foolhardy bloom?

Divided into four parts, conveniently corresponding to the four seasons, Second Nature was chosen by the American Horticultural Society as one of the seventy-five greatest gardening books written. It was the book that put Michael Pollan’s blip on the radar.

Pollan’s attraction, in part, is his laid back take on the environment. Consider: Eat Food. Not Too Much. Mostly Plants. Not exactly the rallying cry of St. Crispin’s Day, is it? Pollan has always struck me as the X-Generation’s  environmentalist: Eating his sushi at Nobu. Planting a tree only to find out after the fact he’s put in an invasive species. Refusing to bow down at the altar of composting (an act he admits borders on heresy in some circles). Or, my personal favorite, smirking at the pretensions of Thoreau playing at hermit in the forest. Pollan makes environmentalism accessible to the masses.

environmentalist: Eating his sushi at Nobu. Planting a tree only to find out after the fact he’s put in an invasive species. Refusing to bow down at the altar of composting (an act he admits borders on heresy in some circles). Or, my personal favorite, smirking at the pretensions of Thoreau playing at hermit in the forest. Pollan makes environmentalism accessible to the masses.

Second Nature is the rare gardening/environmental book in that it is concerned with the real work of gardening. What many see as mundane tasks – mowing the lawn, weeding, composting and planting – these gain greater social and political significance in Pollan’s hands. He shows them to be more than simple acts which result in pretty landscapes or homegrown tomatoes in summer. Second Nature calls upon readers to form a backyard environmental movement.

At the same time it provides a visceral scrapbook of what happens inside of a garden, embracing the Sisyphean cycle of planting, growing, harvest and death that is repeated yearly in backyards across the country. Pollan’s genius is that he views the garden as both a micro- and macrocosm. Like Voltaire, he urges us to tend to our own garden. But he also applies this same philosophy to our greater environmental concerns. He points out that, having taken the step to cultivate the earth, we have taken on the responsibility of managing it. We have insinuated ourselves into nature, irrevocably altering the “natural” course, which means we cannot step out and expect an anthropomorphized version of “Nature” to step back in as if there had been no interruption. We cannot make the mistake of romanticizing nature, the virgin forest or the primeval landscape. We must learn to work with what we have… what in many ways we have wrought. Ultimately, the habits which make a good gardener, he believes, will make good environmentalists.

The gardener doesn’t take it for granted that man’s impact on nature will always be negative. Perhaps he’s observed how his own garden has made this path of land a better place, even by nature’s own standards. His gardening has greatly increased the diversity and abundance of life in this place. Besides the many exotic species of plants he’s introduced, the mammal, rodent, and insect populations have burgeoned, and his soil supports a much richer community of microbes than it did before….

The gardener doesn’t feel that by virtue of the fact that he changes nature he is somehow outside of it. He looks around and sees the human hopes and desires are by now part and parcel of the landscape. The “environment” is not, and has never been, a neutral, fixed backdrop; it is in fact alive, changing all the time in response to innumerable contingencies, one of these being the presence within it of the gardener. And that presence is neither inherently good now bad.

By constantly shifting his perspective from the forest to the trees and back again, Pollan provides a larger action plan which can be implemented at a truly grass-roots level. The genius is that he does so without ever stepping outside of his own garden. In Second Nature he is not an environmental prophet, but another pilgrim on the journey. Sometimes misstepping, yet still doggedly making his way. Trowel in hand.

I agree. Winter is the perfect time for planning, reading, etc. Love that you included your own pic!

LikeLike